by Andy O’Brien

When the call went out for the first state convention of the Maine Anti-Slavery Society, in August of 1834, abolitionists around the world were celebrating the official emancipation of 800,000 enslaved people in the British West Indies. The kingdom that launched the transatlantic slave trade had abolished slavery in its colonies, providing a major boost to the growing anti-slavery movement in the United States.

African Americans were greatly inspired by the Haitian slave insurrection that overthrew the French colonial slaveocracy in 1804, and it was clear that Haiti’s example played a role in the British emancipation. Colonial authorities grew nervous as Black workers revolted, launched strikes and otherwise resisted their rule. A general strike in the sugar fields of Jamaica quickly evolved into the largest slave rebellion in Jamaican history between 1831 and 1832.

The Black community in Portland greeted news of the emancipation with jubilation, and it’s possible there were celebrations of this earthshaking event in the small Black neighborhood on Munjoy Hill. As Professor Tom Zoellner writes, “August First Day” became more meaningful to African Americans than the Fourth of July and was celebrated across the U.S. with picnics, speeches, dancing, hymns and marches until the Civil War.

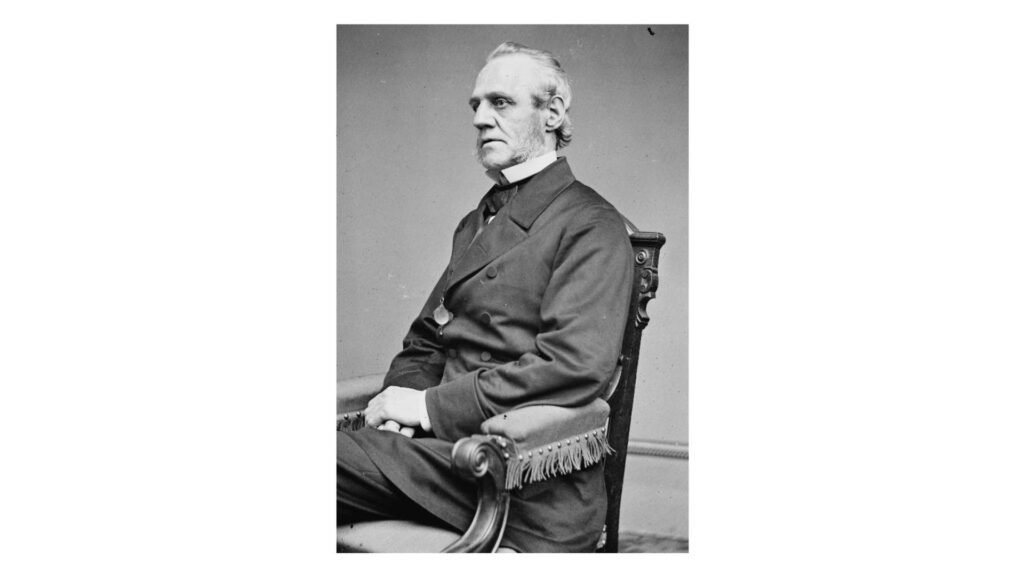

Abolitionist organizer Samuel Fessenden was thrilled to book one of the heroes of the emancipation fight, British Member of Parliament George Thompson, as the keynote speaker of the first Maine Anti-Slavery Society Convention in October of 1834. The 30-year-old Thompson was known as one of the greatest anti-slavery orators and human-rights activists of the era. After Parliament passed the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833, William Lloyd Garrison invited Thompson to the U.S. to electrify the masses and recruit more abolitionists to the cause.

As handbills promoting the gathering appeared all over Maine towns, anti-abolitionist newspapers condemned Thompson as a “foreign agitator” seeking to stir up trouble. Prior to his appearance, the Democratic Augusta Age denounced Thompson as a “mischief-maker coming across the ocean to teach Americans their political duties.” It blasted abolitionists as a “CRAZY HEADED SET OF FANATICS” and suggested anti-slavery activism should “be at once crushed in the bud.”

When Thompson arrived in Portland on Oct. 12, Fessenden showed him around the city and accompanied him to church. They also visited Black congregants at the Abyssinian Meeting House on Newbury Street.

“This was the first time I had ever worshiped in a place, exclusively appropriated to colored persons; nor had I ever, on any occasion, seen so many assembled together,” wrote Thompson. “I analyzed my mind with some anxiety, to discern if, in these entirely new circumstances, any feelings of prejudice were called forth. I can with truth declare, that I experienced none. The attention paid to the services was apparently deep.”

Thompson returned to the Abyssinian two weeks later to deliver a speech before a packed house. He lectured the Black congregants about “exhibiting a pure and blameless conduct” in order to make a good impression on the white population and further the cause of abolitionism. He later described his audience as “decent and devout,” displaying “intelligence and respectability.”

Leading the meeting were two African American pastors: the Rev. George H. Black, who went on to lead the first Independent Baptist Church at the historic African Meeting House in Boston; and the Rev. William C. Monroe, an Underground Railroad conductor, associate of the militant abolitionist John Brown, and co-founder of Noyes Academy, an interracial college in New Hampshire that was burned down by a white mob in 1835.

Black Portland businessman Reuben Ruby was so inspired by Thompson’s speeches that he and his wife Rachel named their fifth child George Thompson Ruby. George Ruby became a prominent labor leader and a state senator in Texas after the Civil War. They named another son William Wilberforce Ruby, after another British politician who led the movement to abolish the slave trade. William Ruby went on to become the first — and possibly only — Black officer elected to the Portland Fire Department, back when those positions were filled at the ballot box.

The Wednesday following that meeting, Thompson joined nearly 100, predominantly white, male delegates at the first convention of the Maine Anti-Slavery Society in Augusta. A special committee drafted and unveiled the new society’s constitution and it was debated point by point. In its preamble, it argued that the “most High God” had made everyone on the face of the earth of “one blood” and endowed them with certain inalienable rights, among which are “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.” It further stated that slavery was “a gross violation of the law of God” and that it was everyone’s duty to “do what they can to put an end to this system of oppression.”

However, the document made clear that slaveholders were not evil; they were simply misled. The society’s founders eschewed forming a political party and vehemently opposed using force against slaveholders to free enslaved people. Instead, they naively believed they could use the power of truth and love to convince slaveholders of their sins and make them see the light.

“We hear a voice from God, saying, ‘Thou shalt not hate thy brother in thy heart; thou shalt not in any wise rebuke thy neighbor, and not suffer sin upon him!’” they wrote. “The slaveholder is our neighbor. He is guilty of a great sin before God, in trampling his brother under foot, because possessed of a skin not colored like his own. We must charge him with his guilt, or God will not hold us guiltless. We must reprove him, or we become partakers in his sin.”

The Maine Anti-Slavery Society also resolved to support free African Americans by promoting “the intellectual, moral and religious improvement of the free people of color and … correcting prevailing and wicked prejudices” while helping them achieve “equality with the whites in civil, intellectual and religious privileges.”

Ruby, one of the few Black delegates to the convention, strongly agreed that education and moral uplift for African Americans was the way to overcome white racial prejudices. However, as historian Edward O. Shriver noted, aside from supporting some individual African Americans and promoting the establishment of Black schools, the white-led society primarily focused on the plight of enslaved African Americans in the South and did very little to help free Black Mainers attain equal rights in their own backyard. Perhaps these factors drew Ruby away from the Maine Anti-Slavery Society and prompted him to focus instead on the Black-led “Colored Convention” movement.

When it was time for Thompson to speak in the evening, he held up a copy of the Augusta Age and asked if “the good people of Augusta” supported such a paper. He read the editorial condemning him as a “foreign agitator.” As the editor himself sat anxiously in the audience, Thompson proceeded to deliver a rhetorical thrashing in front of his peers. The editor “bit his lips, whistled, and left the room,” according to the Rev. J.T. Hawes.

Several anti-abolitionist men followed the editor and gathered at nearby Roger’s Tavern to concoct a plan to raise a mob and break up the meeting if Thompson continued to show his face in town. The next day, at the convention, a group of five anti-abolitionist men confronted Thompson, calling him “a foreign emissary, an officious intermeddler,” and demanding he leave town before 5 p.m.

“I returned a calm and respectful answer, declining, however, to say whether I should comply with the ‘Notice to quit,’” Thompson later wrote to Garrison. “At dinner, I consulted with some friends, and it was finally arranged that I should abide at Mr. Tappan’s until the remaining business of the Convention was transacted, and then retire to Hallowell, the neighboring town, and lecture there in the evening.”

That evening, anti-abolitionist supporters of the newspaper showed up at Thompson’s lecture at the Baptist Church in Hallowell looking to start a ruckus, but were “coldly received” by the audience and failed to disrupt the event. However, while Thompson was staying at the historic Tappan-Villes Mansion on State Street (now owned by Kennebec Savings Bank), someone smashed the home’s front windows in the middle of the night. The Hallowell-based Maine Free Press blamed the vandalism on a “certain clan” connected to “the Augusta aristocracy,” but “more justly” called a “mobocracy.” The editor was particularly offended that Augustans had attempted to meddle in Hallowell’s affairs.

“We can raise our own mobs and riots full as often as we have occasion for them, without the assistance of other people,” the Free Press declared. “We therefore wish our neighbors to stay at home and not offer us any assistance in this line until they are called for, as it is much more pleasant having this business done, if done it must be, by our own citizens. We also think we can determine when a stranger ought to be mobbed without the advice of our neighbors.”

Following the convention, Thompson spoke to Waterville College students, Bowdoin College students in Brunswick, and 120 women at the Friends Meeting House in Portland. Among the Waterville crowd were students who had attempted to form a college anti-slavery society a year earlier, but were thwarted by the administration (see Radical Mainers, June, 2023). Fessenden, who had two sons at the college, invited a half dozen of the students to sign the Maine Anti-Slavery Constitution, and 39 of them ended up joining the national organization. Following the convention, attendee George L. LeRow, a student at Waterville College, reported to Garrison that “the cause of human rights” was “prospering in Maine.”

“Great summons await the great principles of truth,” wrote LeRow. “The time is hastening when the mighty system of wickedness and legalized soul murder is to cease. God grant his truth may prosper.”

[tagline] You can Andy O’Brien at andy@maineworkingclasshistory.com.