by Andy O’Brien

Originally printed in The Bollard

On a September evening in 1840, a group of abolitionist farmers gathered in the vestry of a Baptist meeting house in the small community of Cornish, New Hampshire. Among them were John B. Chandler, editor of the anti-slavery newspaper Herald of Freedom, and the Rev. John W. Lewis, an African-American Free Will Baptist minister and agent for the New Hampshire Anti-Slavery Society. Unbeknownst to them, the “spirit of mobocracy” was lurking in the town that night.

After a prayer, Brother Lewis was beginning his remarks he was interpreted by loud shouting outside. Suddenly, heavy stones and brick-bats rained down on the roof. One of the attendees went outside to try to reason with the mob.

“We just want the n——!” they shouted back.

The angry drunken men continued shouting racist slurs while they hurled rocks, rang a bell and blew a bugle. Inside, the Rev. Winter had a sick child who was terrified by the racket of the furious rabble. Winter went outside to beg the mob to go home, but they refused. “They damned him, and said they would not desist if it killed him and the child both, and threatened him with stones if he did not get [inside],” the Herald of Freedom reported.

The anti-slavery men ignored the mob and calmly continued the meeting, “relying on God” for the rest of the evening. Brother Chandler’s remarks condemning the selling of rum were particularly relevant that night.

Before the meeting adjourned, the abolitionists “heartily” forgave the men, prayed that God would also forgive them, and departed in peace. As the Herald reported afterward, the attack on the meeting only furthered the group’s resolve and reinforced “the rectitude and justice of old fashioned abolitionism.” Lewis and Chandler left Cornish that evening with about 10 new subscribers to the Herald of Freedom. “Thus God prospers us when we go right, and thus is genuine anti-slavery ‘going down’ in New Hampshire,” the Herald concluded.

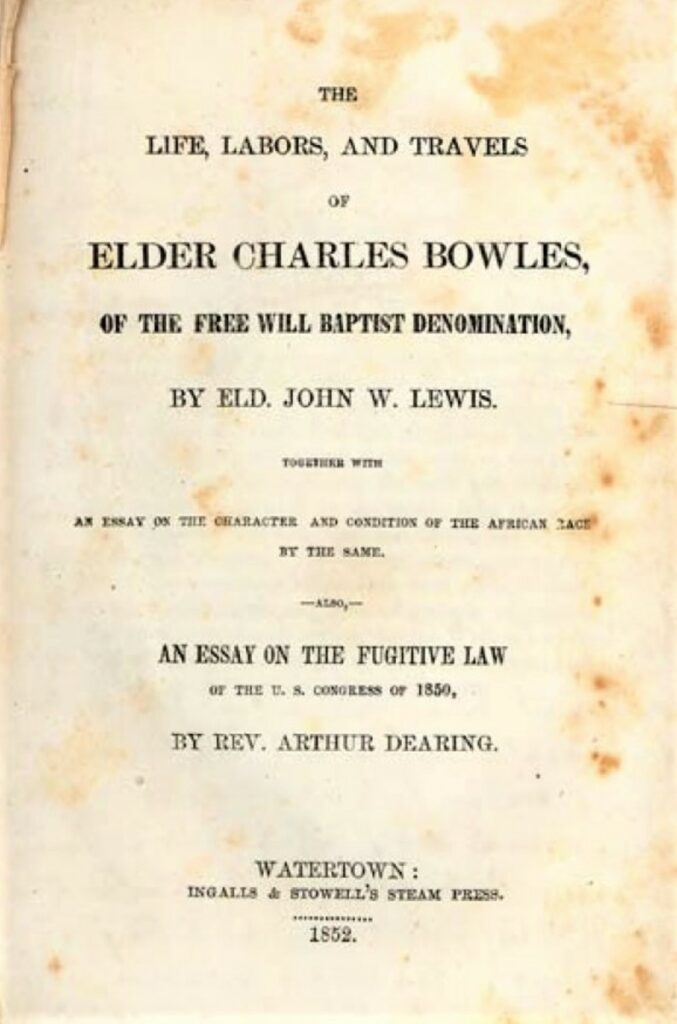

Rev. Lewis was a prominent abolitionist and Freewill Baptist who traveled throughout New England organizing and giving lectures on abolitionism, temperance and civil rights in the decades leading up to the Civil War. In the early 1840s he set his sights on his home state of Maine and embarked on an anti-slavery lecture tour through the back-country towns and hamlets. He partnered with Rev. Amos Noe Freeman of the Abyssinian Church in Portland in 1841 to launch the first Colored Conventions in the state, bringing together African Americans from all over Maine and New Hampshire to discuss ideas, lift up their free Northern brothers and sisters, and liberate their enslaved brethren.

The great abolitionist orator and journalist Frederick Douglass once called Lewis “one of the oldest and ablest advocates for human freedom ever raised up among the colored people of the United States.”

Lewis was born on Dec. 22, 1809, in the village of South Berwick, Maine, near the New Hampshire border. His grandfather, Uriah Williams, served in the Revolutionary War. Williams was 28 when he joined the company of Capt. Nathan Lord in August of 1780, according to historian Benjamin Baker and a group of researchers with the Old Berwick Historical Society.

It’s not clear whether Williams was free or enslaved, or if he had a prior relationship to Lord. As the researchers note, the Lords were a prominent white family in Berwick and owned merchant ships that made several voyages around the world, shipping mostly sugar to Maine. But the researchers surmise it’s also likely they picked up some enslaved workers from Africa or the Caribbean. The Lords were one of a number of Berwick families who had “servants for life” listed on household property tax valuations in 1771.

Williams was the only Black man among the roughly 250 white soldiers from Berwick who served in the Continental Army, according to the historians. He later served under General Peleg Wadsworth at Camden, Maine, for three months, and marched to New York City to defend West Point from the British before returning to Maine in 1781, two years before slavery was officially abolished in Massachusetts (which then contained Maine).

After returning to Berwick, Williams married a woman named Ami Hall in 1788 and they started their life together. Of the town’s 3,900 residents, the African American population comprised only 42 people. Williams worked as a painter and the couple had two children, Grandus and Sarah. Sarah later married a man named John Lewis and gave birth to John W. Lewis in 1809.

The Old Berwick Historical Society suggests Lewis and Williams may have come from a long line of free Black Mainers. They might have descended from a man named Black Will, who won his freedom in 1700 and changed his name to Will Black shortly after. His son, Will Junior, born of a scandalous out-of-wedlock relationship between his father and a white woman, settled his family on Bailey’s Island, in Midcoast Maine. Later, they moved to nearby Orr’s Island, where they were joined by other free Black settlers, forming the second-oldest Black community in Maine. The strait between Bailey’s and Orr’s Islands is still known as “Will’s Gut,” after William Black, Jr.

Perhaps, the researchers posit, another branch of the family chose to use the surname Williams, instead of Black. Like for many African Americans, it’s very difficult to definitively trace their roots back that far.

From a very young age Lewis was deeply religious. He recalled in an 1835 column in a Baptist newspaper that he was in a “state of inquiry & anxiety” until he

“obtained a pardon and forgiveness of sins” at the age of 20 and his “whole heart was lifted to God in thankfulness.” At 12, Lewis traveled to Portsmouth, N.H., to join the Methodist Episcopal Church and was accepted as one of the first Black students at Wilbraham Wesleyan Academy, a Methodist prep school near Springfield, Mass.

At age 23, Lewis was ordained as a Methodist deacon in Philadelphia and briefly held a Methodist ministry in Newark, N.J., in the early 1830s. Then during a visit to Maine he joined the Freewill Baptist Church, one of the first openly abolitionist Christian denominations.

Founded by a New Hampshire Baptist minister named Benjamin Randall in 1780, the Free Will Baptists rejected the fundamental Calvinist doctrine of absolute predestination — that everything that happens has already been predetermined by God. Unlike Baptists, Free Will Baptists preached “free atonement,” which meant anyone could achieve salvation if they repented for their sins. The historic Free Will Baptist Church where Lewis likely got saved still stands today on Main Street in South Berwick.

Lewis joined the Free Will Baptists toward the end of the Second Great Awakening, an intense period of Protestant revival. Church membership exploded as charismatic preachers saved countless souls and sparked religious fervor for moral reforms like temperance and abolitionism.

In 1834, Lewis became the President of the Garrison and Literary Benevolent Association, a Black-led youth organization founded by Henry Highland Garnet, William H. Day and David Ruggles. Controversially, it named itself after crusading white abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison. The Association, which was open to African American boys of “good moral character” ages 4 to 20, was dedicated to promoting abolition and the “moral and intellectual improvement of the rising generation of our race.” Its overriding goal was to “vindicate” the cause of anti-slavery by helping students “distinguish themselves by their good conduct and intellectual attainments.” A typical New York Garrison Literary Society class at a Black public school in 1834 involved about 150 children delivering anti-slavery speeches and reading essays. Shortly after, it was moved to a private venue after one of the school’s trustees demanded it change its name.

Contemporaries described Rev. Lewis as a striking figure. He was a large man with deep ebony skin who was known as a passionate and incendiary evangelist. In 1835, he went to Providence, Rhode Island, where he lit the town ablaze with a series of energetic revival meetings at the historic African Union Meeting House. According to Baker, Lewis engaged a “holistic ministry” that mixed the Gospel with a message of abolition and Black uplift. When he baptized someone, Lewis described how he would have them “pledge and determine to strike, by their moral power and religious influence, at the root of slavery, and not to give over till this Babel of abominations shall fall.” He believed, as he wrote in 1840, that “if the whole church in the north would stand on the broad platform of God’s promises, put all confidence in Him and act accordingly, they would shake the whole foundation of slavery at the south.”

Fellow Mainer and Free Will Baptist minister Silas Curtis described how hundreds of sinners flocked to meeting houses in Providence to hear Lewis’ nightly sermons, with not a single interruption from “pro-slavery men,” as was common at the time.

“It has been enough to cheer the soul of any lover of liberty to hear the converts, all through the revival, in their broken prayers, pleading for their oppressed brethren at the South,” Lewis wrote. “Pure abolitionism goes well in good revivals.”

Historians have credited Lewis’ spirited revivals with the proliferation of Black churches in the city. His work likely provoked a split in the Abyssinian Free Baptist Church, as the more conservative members of the flock fled to Methodist churches while those who “favored religion in strong doses” formed the first Black Free Will Baptist Church in New England, according to historian Julian Rammelkamp.

In 1836, Lewis founded the New England Union Academy, a boarding school for African American children and adults in Providence. Tuition was three dollars per quarter and Lewis taught courses in reading, writing, math, history, philosophy, geography, botany, single and double-entry bookkeeping, and more. Many of the school’s patrons were longtime abolitionist from Maine, including Congregationalist minister George Shepard and businessman Ebenezer Dole of Hallowell, Rev. Benjamin Tappan and merchant G.G. Wilder of Augusta, and several individuals from Lewis’ hometown of South Berwick.

Next month we’ll continue Rev. Lewis’s story, including his founding of the first Black temperance society, his work re-launching the Colored Convention Movement in Maine, and more. I want to thank Benjamin Baker for so generously sharing his research for this column.

Andy O’Brien can be reached at andy@maineworkingclasshistory.com.