by Andy O’Brien

In 1830, a “gentleman from Maine” complained in the abolitionist newspaper The Liberator that there were no schools for the growing African American population in Portland. It’s not clear whether the anonymous man was Black or white, but he provided a vivid description of the kind of racism Black Portlanders endured and the segregationist policies that blocked them from educational opportunities.

“To show you the state of feeling at a glance, a little darling white [boy], four years old, comes from the Infant School, scolding about the little n—— who would sit by him,” the man wrote. “Query — was this born in the white [boy] or instilled? This, sir, is a fair specimen of feeling throughout the State.”

In those days, reform-minded Mainers advocated for a public school system that would ensure every child — regardless of religion, status, economic background or geographic location — could obtain a quality education. Reformers believed these taxpayer-funded “common schools” would provide more opportunities for students of more moderate means, develop an educated workforce for employers and mold children into informed and engaged citizens. However, this right came with a big asterisk — African Americans, whether free or enslaved, were never considered citizens in the eyes of white America.

By advancing arguments that “privileged citizenship,” instead of equality and social justice, the common school movement actually reinforced white efforts to deny civil rights to African Americans, argues Amherst College professor Hillary J. Moss in her book, Schooling Citizens: The Struggle for African American Education in Antebellum America. As a result, she writes, many white people sought to deny Black students the privilege of a public education because “it was a mark of the very citizenship they sought to withhold from African Americans.” Universal public education was yet another privilege they had over African Americans, like the right to vote, job opportunities and access to shelter aboard steam ships.

Even more well-off Black Mainers, like the journalist John Brown Russwurm, found it difficult to get a decent education in Portland as a teen. As Russwurm’s stepmother recalled, it was “rather difficult” in the 1810s to get a Black child “into a good school where he would receive an equal share of attention with white boys.” Russwurm was eventually able to attend private schools and, later, Bowdoin College, but working-class Black Mainers had far fewer options. In some areas with larger Black populations, cities and towns began creating segregated schools.

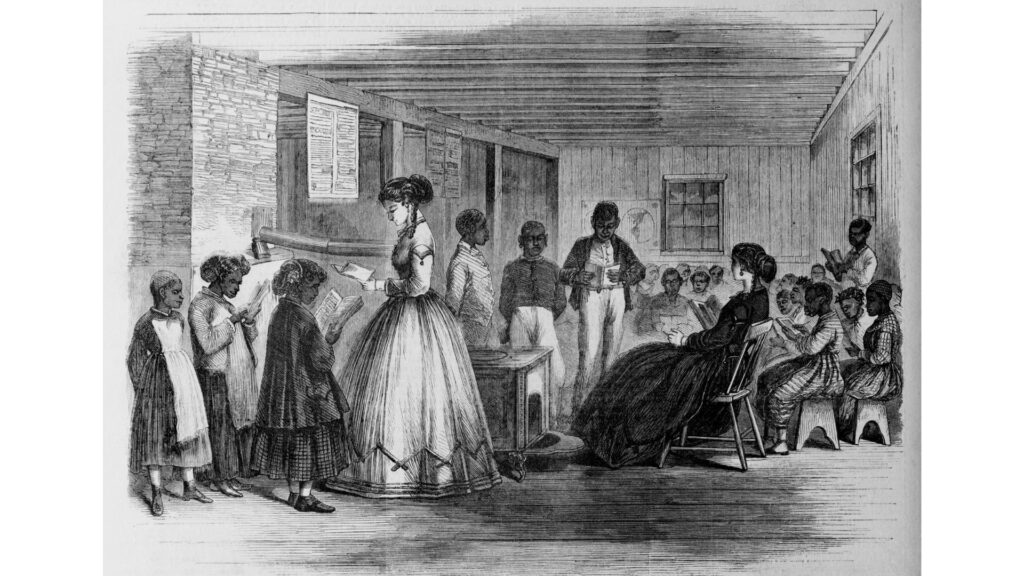

Peterborough, a Black community in Warren, created the first Black school district in Maine in 1823 and, subsequently, its own school house. Edward H. Ellwell wrote in his 1886 history, The Schools of Portland: From the Earliest Times to the Centennial Year of the Town, that a few Black children, including some from Africa and the Caribbean, attended a white school on Congress Street (which later became the North School) in the early 19th century. As the population of African Americans began to grow in tandem with the availablility of maritime jobs, a school for Black children was established in 1833. When the Black school was founded it was one of only 10 “colored schools” in the country, and one of five in cities that funded education for African American students.

According to Elwell, the Black school was located in a back room of the Congress Street Grammar School and had a separate entrance on the side of the building facing Eastern Cemetery, in Portland’s East End. The first teacher at the Black school was a white woman named Mary Maddox. She was succeeded in 1833 by a well-regarded white teacher named Mary O. Haynes, who also taught white children at the Congress Street school.

However, in 1834, the white-led Portland school board wrote in its annual report that it closed the Black school because attendance had dwindled to just one student. The white Portland abolitionist Daniel C. Colesworthy attempted to stir interest in education in a motivational speech before a Black audience a year later, in 1835:

The epithet, “ignorant people,” is often cast upon your race by your enemies. They say “If schools are established among the blacks they are so debased, careless and indifferent, that they will not take pains to attend. You cannot improve their minds. It is not in them to improve.” … Therefore you should be the more anxious to confute their hard and cruel sayings; by being the industrious — more anxious to learn. … I would particularly urge upon parents the importance of teaching their children the necessity of cultivating their intellects. … I see no reason why the children of color cannot come up to the favored whites in point of mental discipline and intellectual сulture. I am satisfied if pains are taken with the young, the day is not far distant, when your children’s acquirements will be equal to those of other children.

School officials in Portland claimed in their report that there was a “lack of appreciation” for the Black school among the African American community, but they neglected to explain exactly why parents pulled their children out of the school. Unfortunately, no accounts by the Black parents are known to exist, but it’s highly likely that Haynes was simply not able or willing to provide the same level of attention to both white and Black students placed in separate schoolrooms. In the meantime, the Abyssinian Church began temporarily holding classes for Black children. Enrollment reportedly rose — an indication that there was still interest in education among the Black community; just not in what the city had to offer.

The following year, rumors spread that white schools were going to start admitting Black scholars. A letter signed “A Citizen,” published in the Eastern Argus on March 3, 1835 attempted to calm the “considerable excitement” stirred up by the rumors:

I have been seriously told that fifteen [Black students] had been admitted to Mr. Jackson’s school, and that one day forty were there! Feeling a little curiosity, I made inquiries at Mr. Jackson’s today and found none there; and more than this, he has not had a colored child in his school since the colored school was discontinued — and has no right to admit them without instructions from the School Committee. I have heard many rumors of their being admitted into other schools, which probably are equally erroneous. Without stopping at this time to discuss the propriety or impropriety of these children being thus admitted to attend some school, I will only remark to those who have manifested so exquisite a sensitiveness upon this subject, that it is but even justice to wait till the event they so much deprecate occurs, before they uncork the vials of their wrath upon this matter.

Finally, after more than a year, the Black school was reestablished with a new full-time teacher in a small building behind the Congress Street School, Ellwell wrote. The new teacher, James M. Dodge, had 43 students and much better attendance, according to school board minutes. Board members reported that Black parents and their children were more engaged in education, with a “zeal and ambition” for advancement. Meanwhile, however, attendance continued to be a problem, but the school board attributed some of the problem to “their great want of suitable books.”

After visiting the Black school in August of 1837, a white abolitionist, the Rev. David Thurston, reported in the Christian Mirror newspaper that Dodge was “devoting himself with unwearied diligence” to his students. He added that the school was apparently “exerting a very great and salutary influence” on the students. However, he added, the white community, including abolitionists, didn’t appear to be interested in providing help to their Black neighbors.

“We see the deadly influence which slavery is exerting upon is, in leading us to overlook their rights. And to disregard the interests of the colored Americans,” wrote Thurston. “This spirit of caste, as hostile to the spirit of the Gospel as enmity is to love, oppresses our brethren here. It shuts them out of honorable and lucrative employments. It closes against them our institutions of learning.”

A reader with the initials “J.W.” took exception to Thurston’s comments. “I wish … to state distinctly that, as a city, we are now doing more for the education of our colored children than we are for the education of any other children in the city,” J.W. wrote in the Portland Transcript. “That is, the city provides a school expressly for these children — and supports a teacher as well qualified for his task and as devoted to his duties, as any other teacher in the city.”

By segregating about 50 Black children in a separate school with one staff member, J.W. argued that the city was doing more for them than white children. “For were the question proposed to the school committee tomorrow, to establish a male school for so small a number of white children, it would be rejected at once,” J.W. wrote. “I know there is a want of interest in colored people — but not a greater want of interest in these, than in the poor and vicious of our white population. Therefore, I believe that this interest is owing to the fact that our people are absorbed in their own anxieties, interests and pursuits, and not to any prejudice against any portion of our inhabitants.”

While it’s true that Portland did more to provide an education to Black students than most other cities, the white community would not even entertain the idea of integrating Black and white students.

As researcher Jonna Boure Ellis notes, it wasn’t clear how much of the funding for the Black school came from public coffers and how much was provided by private, charitable donations. She suggests the district may have hidden this aspect of its budget because of the controversy over using public funds to educate the city’s small Black population. “The low priority assessed to the school by the school committee proves this point, and perhaps it became necessary for the Abyssinian Society to step in financially,” Ellis wrote.

Then, in 1842, the Rev. Amos Noe Freeman — an African American Presbyterian minister, educator, civil rights activist and Underground Railroad conductor — arrived in Portland from New Jersey to take over as the first full-time pastor of the Abyssinian Church. Under his leadership, Black education in the city would dramatically improve. Next month: the story of the Rev. Freeman and a new era of Black politics in Portland.

Andy O’Brien is the communications director for the Maine AFL-CIO. You can reach him at Andy at maineworkingclasshistory.com.