On a spring evening in May, 1835, a group of Black Portlanders gathered at the Abyssinian Meeting House on Newbury Street for what they described as “a respectable meeting of colored citizens.” The purpose of the gathering was to choose delegates to send to the Fifth Annual Convention of the Free People of Color — a Black-led organization dedicated to abolition and equality — in Philadelphia the following month.

The young Abyssinian church still didn’t have a full-time pastor, but its part-time white minister, Samuel Chase, gave the opening address. Black barber Chris C. Manuel was elected meeting president and Abyssinian member Franklin G. Pierre was the secretary.

The attendees selected businessman Reuben Ruby and Baptist preacher George H. Black, who owned a clothes-cleaning business on Federal Street, to represent Maine at the national convention. Ruby, who’d helped to establish the Maine Anti-Slavery Society the previous fall, saw an opportunity to strategize and organize for racial justice with other prominent free Black men.

Although the white abolitionists meant well, they had no idea what it meant to live as a free Black American in the early republic. They held all the leadership roles in the Maine Anti-Slavery Society and had little interest in developing Black leaders in the movement. They focused almost exclusively on freeing African Americans in the South from bondage, while largely paying lip service to the struggles of their Northern free Black neighbors.

The “Colored Conventions” provided a unique opportunity for free African Americans from across the country to organize and build power to fight for educational opportunities, abolition, temperance and equal rights. It was a chance to cultivate Black leaders in a white-dominated society structured to prevent them from achieving power and influence.

Like the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the Colored Convention Movement was founded in response to racist white violence. In the 1820s, free African Americans and Black refugees fleeing bondage in the South began settling in Cincinnati, Ohio. This angered Irish immigrants, who competed with them for low-wage jobs and housing. In June of 1829, city leaders announced that Black residents were required to post surety bonds of $500 ($16,500 in today’s dollars) within 30 days or be expelled from the city and state.

Later that August, mobs of white men, primarily Irish immigrants, raided the densely populated Black neighborhood along the river and dragged residents out of their homes. As the Cincinnati Sentinel reported:

Some two or three hundred of the lowest canaille of our city, animated by the prospect of high wages, which the sudden removal of fifteen hundred laborers from the city, might occasion, thinking the law not rapid enough in its movements, in getting rid of the blacks, during the several nights made the most violent assaults, in great numbers upon the blacks, who reside in Columbia street, throwing stones, demolishing houses, doing every other act of riotous violence. On Saturday evening, the blacks who had hitherto remained in their houses, despairing of receiving the protection of the law, fired upon the mob, killed one man, and severely wounded two others. This operated as a quietus.

Mayor Isaac G. Burnet dismissed charges against the gunman and nine other Black men, determining that they had acted in self-defense. Eight white men who participated in the riot were tried and fined. But in the end, the white mobs were successful in driving out their Black neighbors. Following the rioting, between 1,100 and 1,500 Black residents left the city, many of them fleeing to Ontario, Canada.

The following year, free Black leaders gathered in Philadelphia for the first national Colored Convention, where they discussed the racial violence in Cincinnati and debated the merits of founding a colony in Canada to provide a refuge for free Black Americans. While some Black leaders expressed support for forming free Black colonies outside the U.S., the delegates firmly and vehemently opposed the white-led American Colonization Society and its scheme to encourage African Americans to emigrate to West Africa. Convention organizers invited some prominent white abolitionists, like William Lloyd Garrison, Benjamin Lundy and Arthur Tappan, to address the conventions, but colonizationists were banned.

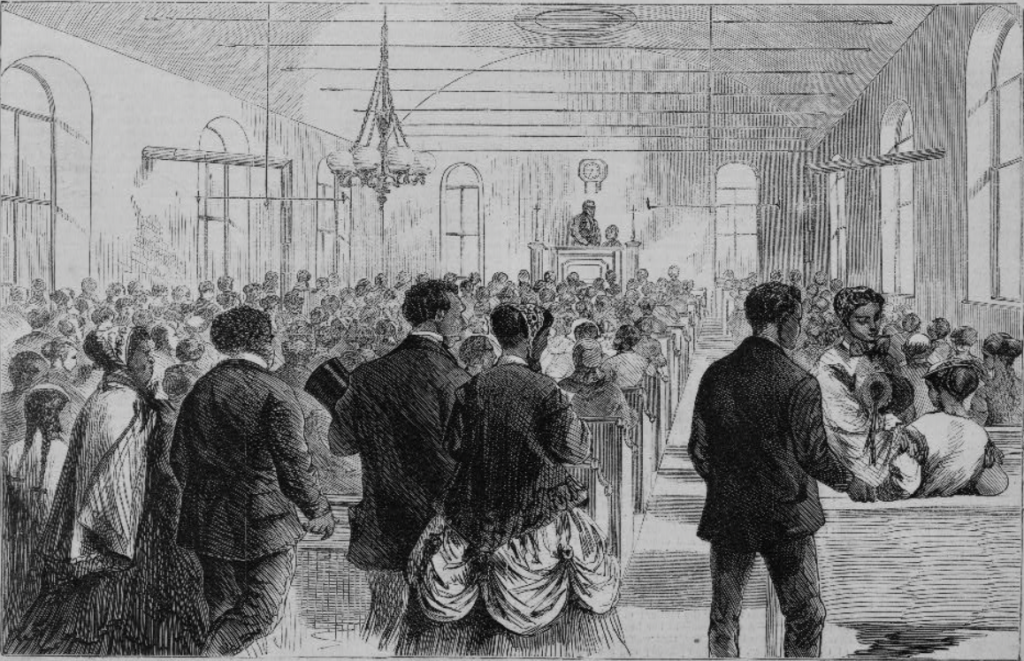

As the Black convention movement grew, it became primarily focused on strengthening African American civic participation and self-improvement, and reforming racist laws that prevented them from exercising their full citizenship rights. More than 200 state and national Colored Conventions were held at churches, city buildings, lecture halls and theaters between 1830 and the 1890s, laying the groundwork for future civil rights struggles in the 20th and 21st centuries led by the NAACP, the Congress of Racial Equality, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and the Movement for Black Lives, to name a few.

Thousands of free Black men and women — including church leaders, educators, doctors, newspaper editors, writers and entrepreneurs — traveled to conventions in cities across the country to network, strategize, and organize for equal education, fair wages and voting rights. Author and historian William Wells Brown, abolitionist Charles Remond (who toured Maine in the 1830s), journalist and Presbyterian minister Samuel Cornish, the anti-slavery orator Frederick Douglass, Othello Burghardt (grandfather of the great intellectual W.E.B. Du Bois), and Charles Langston (grandfather of the Harlem Renaissance poet Langston Hughes) all played leading roles at Colored Conventions.

Delegates encouraged the creation of Black newspapers to combat racist mischaracterizations in the white press. They even took steps to create a centralized, national Black media organization in the 1840s. These initiatives were inspired by Jamaican-born Mainer John Brown Russwurm and Cornish, who co-founded Freedom’s Journal in 1827, the first Black-run newspaper in the United States [see Radical Mainers, Nov. and Dec. 2022]. Ruby was an agent for Freedom’s Journal and distributed it around Portland’s Black community during its brief, two-year run. He likely identified with its focus on educational uplift, moral consciousness and self-help, as he had co-founded Portland’s first Black church on similar principles. More than anything, the conventions and the Black press were about building a community across geographic boundaries, creating a national dialogue about racial justice, and pushing the country to live up to its revolutionary principles of freedom and equality.

To Die As Martyrs for the Cause of Freedom

When Black, the convention delegate from Portland, attempted to purchase a ticket to Boston on the steamer ship Mcdonough on May 25, 1835, he experienced an injustice that was all too common in Maine in those days. The ticket agent said Black was prohibited from staying in the ship’s cabin due to the color of his skin. When he complained, he was told he would not be permitted to board the ship unless he agreed to the conditions. Rather than stand on the ship’s deck the whole way to Boston, Black refused.

“This, in respect to myself and my character, I could not do, though obliged to postpone my trip at considerable inconvenience and disappointment,” Black later wrote in a notice published in the Liberator newspaper.

It’s not clear how Black eventually made it to the convention in Philadelphia, but it wasn’t on the Mcdonough. At the convention, Black and Ruby joined like-minded delegates to chart a new course for the movement. Although this was Ruby’s first national convention, he must have already had a reputation as an effective leader, because those assembled immediately selected him as the convention president.

Over the five days of the convention, delegates passed resolutions to petition governments for the right to vote and equal education. They encouraged the creation of Black literary societies and trade schools to train African American youth to become shoemakers, sail makers, carpenters, tailors, and practitioners of other lucrative trades traditionally reserved for white men. Black made a successful motion to recommend that June 25 be designated as a day of fasting and prayer on behalf of their “suffering brethren in slavery.”

But the main purpose of the convention was to form the American Moral Reform Society (AMRS), a national organization dedicated to education, temperance, economy and universal liberty. Like Ruby, AMRS co-founder and businessman William Whipper believed racial prejudice could be overcome if African Americans conformed to white standards and improved “their mental, economic, and moral situations.” Through non-violence, persuasion and example, Whipper reasoned that free Black citizens could gain social acceptance in white society.

Whipper co-authored the society’s “Declaration of Sentiments,” which argued that the “excellence of attainment in the arts, literature and science” of ancient African civilizations once “stood before the world unrivaled.” But the enslavement of their ancestors “led to a system of robbery, bribery and persecution offensive to the laws of nature and of justice.” In God’s eyes, the Declaration continued, unjust laws that deprived African Americans of liberty and basic rights were “wholly null and void” and should be immediately repealed.

By supporting the declaration, the delegates declared their willingness to die “as martyrs” for the cause of “freedom to all mankind.” Membership in the AMRS would be open to both white and Black men who pledged to join the moral crusade to uplift African Americans and fight to end slavery and racial prejudice.

Black leader James Forten of Philadelphia was chosen as the Society’s president and Ruby was selected as one of its vice presidents, along with the newspaper editor Cornish and other Black leaders.

On June 9, following the convention, Ruby and seven other Black travelers publicly thanked Captain Vanderbilt, of the steamboat Lexington, “for his kind treatment” of them during the vessel’s voyage from New York to Rhode Island and Maine. They recommended that other Black travelers use his services. Ruby’s notice ran in the Liberator alongside Black’s account of discrimination on the Mcdonough, with an editor’s note: “Here is different treatment! Shame.”

The two notices appeared to suggest a boycott of racist businesses, but it would take another few generations for Black activists to use this tactic effectively.

You can reach Andy O’Brien at andy@maineworkingclasshistory.com.