By Andy O’Brien

Originally appeared in the July, 2023 issue of The Bollard

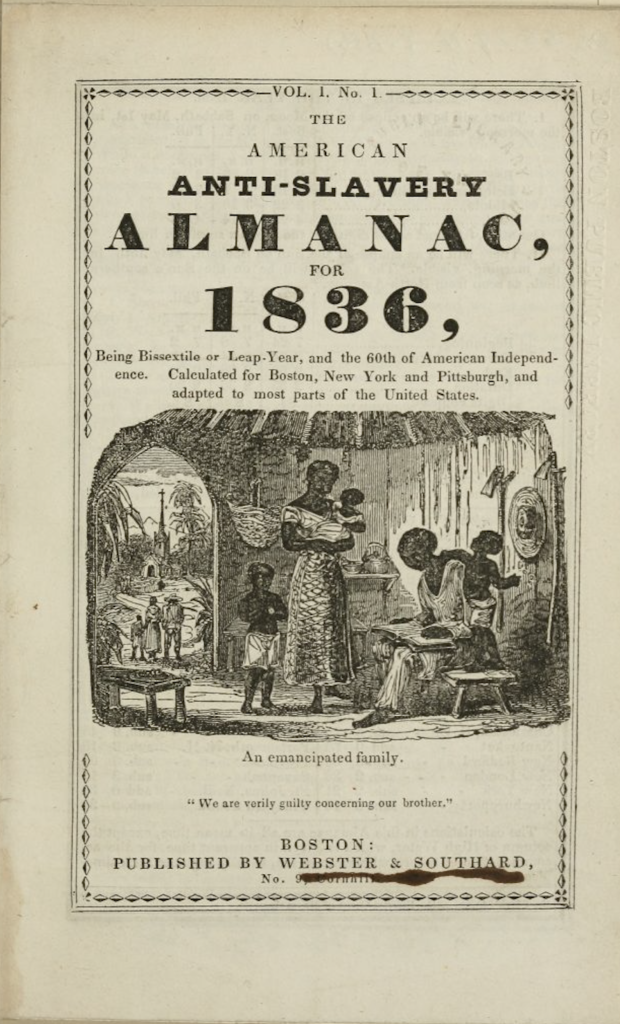

On Aug. 16, 1834, Maine abolitionists put out the call to anti-slavery activists across the state to come to Augusta on the third Wednesday of October to “unite in fervent prayer to Almighty God to direct and bless our efforts to abolish slavery throughout the land.” During the nearly two years since William Lloyd Garrison’s historic visit to Maine, abolitionists had begun forming local anti-slavery societies, and they had finally garnered enough strength to launch a statewide chapter.

Several of Maine’s abolitionist leaders were wealthy and prominent men in their communities, though their views were considered eccentric to most Mainers. They were entrepreneurs, merchants, land speculators, clergy, physicians, lawyers and newspaper editors. Founding members of the Portland Antislavery Society included its President, Prentiss Mellen, the first Chief Justice of the Maine Supreme Judicial Court; attorney and politician Samuel Fessenden; successful businessman Nathan Winslow; journalist and nationally renowned humorist Seba Smith; Methodist minister Gershom F. Cox; and printer Daniel C. Colesworthy.

Colesworthy ran a bookstore on Exchange Street and edited a series of youth and literary newspapers including The Youth’s Monitor and the Portland Tribune. He also published the Portland City Directory and African-American writer Robert Benjamin Lewis’ groundbreaking Black historiography, Light and Truth (see the Sept. 2022 Radical Mainers for more on Lewis).

Nathan Winslow and his wife, Comfort, were two of the most prominent abolitionists in the city. As an artisan, merchant and inventor, Nathan embodied the transition from independent craftsman to industrialist that characterized the emerging Industrial Revolution. An inventor of one of the earliest cookstoves and innovator of food processing technology, he founded the first wood stove foundry in Maine and the first corn-canning operation in the United States. The Winslows were devout Quakers who not only opposed slavery, but also opened their home to traveling abolitionist speakers and fugitive slaves on the Underground Railroad.

The writer and activist John Neal called Nathan Winslow a “desperate unrelenting Quaker-abolitionist.” He recalled an incident when Winslow refused Neal’s assistance in the face of a hostile anti-abolitionist mob outside an abolitionist meeting in Portland. The mob “pitched” Winslow “headlong into the gutter” and rolled him over in the mud before letting him escape.

Comfort hosted meetings of the Portland Female Anti-slavery Society in their home. At its annual meeting in 1834, a five-year-old Black girl recited a long poem about the condition of African Americans “with great propriety and fine effect.” The white women resolved to meet regularly to instruct the “female colored population in knitting, mending, and various kinds of needle work.” In the paternalistic fashion typical for the time, the women pledged to “elevate the character of an unjustly degraded race.”

Nathan Winslow, his brother Issac, Rev. David Thurston of Winthrop, 25-year-old attorney and journalist James Frederick Otis of Portland, and Quaker businessman Joseph Southwick of Vassalboro were among the 60 delegates from New England, Ohio, New York and New Jersey who attended the first convention of the National Anti-Slavery Society in Philadelphia, in December of 1833. Shortly after, Southwick and his wife, Thankful, who hailed from an affluent Quaker family in Portland, moved to Boston, where she became a powerful voice for women’s rights and abolition alongside such luminaries as writer and sometime-Mainer Lydia Maria Child (see Radical Mainers, Jan. 2023).

Two years after signing the American Anti-Slavery Society’s declaration of sentiments, James F. Otis, who was born into a wealthy and well-respected Boston family, became a pariah in the movement after he publicly denied he was an abolitionist and renounced his membership in the Society. In a letter to the Richmond Enquirer in September of 1835, Otis, who once glowingly compared Garrison to Jesus Christ, claimed the Society’s leaders deceived him about their radical intentions. While staying in the White Sulfur Hot Springs of Virginia nursing his “very violent, acute rheumatism,” Otis claimed he shut his mouth about slavery as soon as he saw “the entire South in a flame of excitement upon the bare mention of it.” He argued that Northern abolitionists were only adding “fuel to the flame,” and that their demands would actually hinder efforts to end slavery

The fervently anti-abolitionist Portland Argus had a different take.It claimed Otis had been in Virginia trying to stir up trouble and was exposed as an anti-slavery zealot. When he was arrested and brought before the local magistrate, the Argus claimed Otis “set up such piteous begging and well-feigned protestations of innocence, disavowing all connexion” with the abolitionists. It further claimed the magistrate let him off, and that Otis swiftly “out-ran the mail itself, and escaped the humble honor of ‘tar and cotton’” with an angry local judge in hot pursuit. From then on, Otis was known as “Benedict A. Otis” in the movement.

The Rev. David Thurston was an anti-slavery Congregational minister at a time when the Congregationalist Church’s leadership was fervently opposed to the abolitionists. Instead, the church supported the abolitionists’ mortal enemies, the American Colonization Society. Between 1833 and 1834, Thurston embarked on a lecture tour to set the Maine countryside afire with his searing abolitionist sermons. Although the audiences were small, he undoubtedly won over a few souls. As he once wrote:

[God] has made it our duty always to act from religious principle. We are not authorized to act from a principle of selfishness or party interest today, and of benevolence tomorrow. We are to be holy always in all we do. We are required to be as holy, that is to have a pure desire to honor God and to promote the welfare of men, at one time, as at another, on the second and third days of the week, as on the first.

Thurston was an passionate organizer, and when he helped found the Winthrop Anti-Slavery Society in May of 1834, he was also elected its first President. In addition to the male-run Society, he helped launch female and juvenile chapters in the town. Thurston tried to pull his parishioners into the movement and held a monthly concert of prayer for enslaved people at his church. However, his radicalism caused a “division” among his congregants that eventually led to his dismissal.

The second anti-slavery society in Maine was founded by merchant Ebenezer “Deacon” Dole and his brother, Daniel, at his Hallowell home, which still stands today an Second and Lincoln streets. Deacon Dole was a friend of Garrison’s — he helped bail him out of jail in 1830 and hosted him in his home during Garrison’s 1832 visit to Hallowell. It’s likely that Deacon Dole was also a conductor on the Underground Railroad. In November of 1835, an enslaver named Ambrose Crane, of St. Marks Florida, accused Dole of “stealing” his wife’s “property” by providing asylum to a young African-American girl who served as the Crane family’s nanny while they were visiting Hallowell the previous August.

“Now Sir I have only one word to say (at present) on the subject that is, to return my property to me without delay or expense,” Crane wrote to Dole, “or I pledge you my word it shall cost you 3 times the value of the girl, besides I will advertise you & your compatriots in this nefarious transaction in every state in the union & offer such a reward as will probably give me the pleasure of seeing you here when I could get more for exhibiting you a month than you have made all your lifetime…”

Little else is known about the girl or if she ever made it to freedom, but it doesn’t appear the threat worked. Deacon Dole’s nephew, Daniel, became a missionary in Hawaii. In 1893, Daniel’s son, Sanford Dole, backed an American-led coup d’état that overthrew the islands’ indigenous monarchy and installed him as President of the new Hawaiian Republic. Another of Deacon Dole’s nephews, Charles Fletcher Dole, became a radical Unitarian minister, anti-imperialist and outspoken proponent of racial and gender equality. Charles’ son, James Drummond Dole, on the other hand, went to Hawaii in 1899 to join his cousin Sanford and help establish the massive Dole pineapple empire that made them fabulously rich.

At the same time, conservative activists were also organizing mass meetings to stop the spread of abolitionist sentiment. A large crowd of anti-abolitionists packed a meeting in Portland in August, 1835 to condemn the rabble-rousers. They expressed fear that abolitionists would “excite the passions of the slaves” and “make free persons of color not only dissatisfied with the condition in which they were placed by the established orders of society, but to make them repine and murmur at the order of Providence which by an indelible character has marked them and will forever mark them as a peculiar people.”

As historian Louis Hatch writes, the assembled anti-abolitionists resolved that although slavery was morally wrong, “its immediate eradication would produce evils which cannot be contemplated without dismay.” Instead, those gathered put their trust in “the generous and chivalrous South” to gradually rid itself of slavery over time. The group appointed a representative from each church parish in the city to formally request their churches forbid anyone from lecturing in their meeting houses about the abolition of slavery.

Like reactionary conservatives today, the Portland anti-abolitionists blamed the growing anti-slavery sentiment in the city on outside agitators: “itinerant, intermeddling foreigners, impertinently obtruding themselves upon our people” and seeking to stoke a slave insurrection and civil war. When it was announced that the keynote speaker of the upcoming Anti-Slavery Convention was none other than famed British abolitionist George Thompson, the opponents of abolition had the perfect villain for their xenophobic conspiracies.

Andy O’Brien is the communications director for the Maine AFL-CIO. You can reach him at andy@maineworkingclasshistory.com.