By Andy O’Brien

Originally appeared in the June, 2023 issue of The Bollard

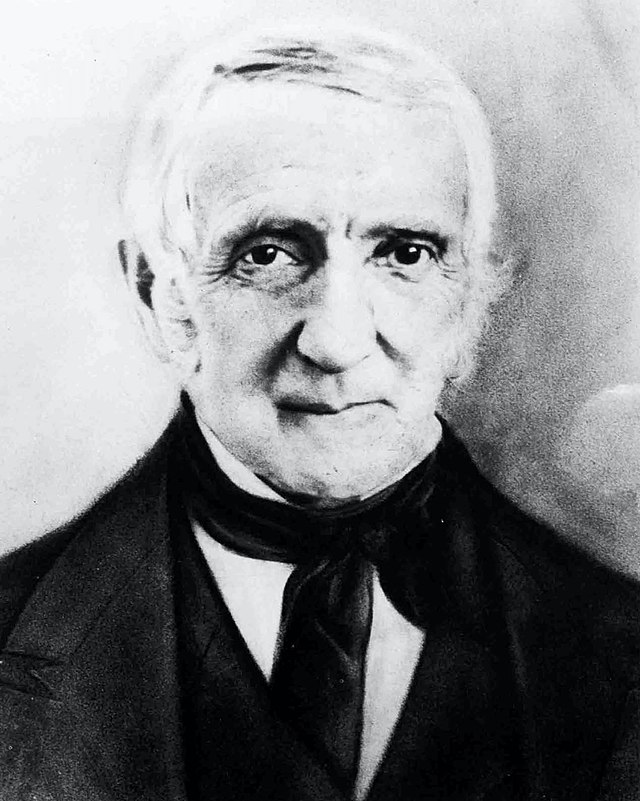

Colby College President Jeremiah Chaplin

In June of 1833, the rabble-rousing abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison arrived at Waterville College (now known as Colby) for the last stop on his lecture tour of Maine. He was invited to speak to the student body as the guest of the college’s president, the Rev. Jeremiah Chaplin. Little did Chaplin know that Garrison’s appearance would set off a chain of events that would result in his untimely resignation from the college a few weeks later.

Chaplin was a strict Calvinist, a deep thinker and a scholarly theologian. He was “thin, spare and tall, with sharp, angular features and a penetrating eye,” according to Colby College historian Ernest Cummings Marriner. Originally the pastor of the Danvers Baptist Church, in Massachusetts, in 1818 he was offered the position of Professor of Divinity at a new Baptist school then known as the Maine Literary and Theological Institution. When Chaplin arrived with his wife, Marcia, and their children by longboat up the Kennebec River, the future site of the college was still rugged forest land, so during the first year, classes were held in the Chaplins’ rented house. Three years later, the institution was renamed Waterville College.

The incendiary abolitionist journalist Elijah P. Lovejoy graduated as valedictorian of the Class of 1826 and went on to become this country’s first free-speech martyr after being gunned down by a pro-slavery mob in Alton, Illinois, in 1837. When Lovejoy was penniless and trying to make his way out West, Chaplin helped him pay for his passage to St. Louis. A year after his murder, Chaplin remembered Lovejoy as “never chargeable with making light of sacred things.”

In 1824 the college founded its Literary Fraternity to provide a forum for debates, and it didn’t shy away from hot-button issues like the slavery question. While staying at the Eagle Hotel in Maine, Lovejoy came across a pamphlet containing a poem delivered by a young Maine politician named Richard Hampton Vose at the Literary Fraternity’s anniversary gathering on July 26, 1831. Lovejoy was so inspired that he printed a passage from the poem in his Liberator newspaper:

Is Freedom safe, when men may wear the chain

On her own soil, and cry for help in vain?

When ye can hear the oft repeated tale

Of Afric’s wrongs, which cheeks no longer pale?

As though it were some idle, fond conceit,

Contrived to frighten those it could not cheat!

Shame to the land, whose motto ought to be,

All men are equal, by their nature free

After Garrison’s lecture, the students were so fired up that they held a mass meeting the following Independence Day, July 4th, 1833, to draft a constitution for a new Anti-Slavery Society. The 32 signers of the organization’s constitution were among the tiny elite group of (predominantly) men who had the privilege to go to college in those days. They were future ministers, missionaries, intellectuals, professors, attorneys, businessmen, authors and newspaper editors. The Society’s founding document drew on the nation’s revolutionary heritage: “Believing that all men are born free and equal, and possess certain unalienable rights, among which are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, and that in no case consistently with reason, religion, and the immutable principles of justice, can one man be the property of another…”

The enthusiastic cheers and revelry at that July 4th meeting reached the ears of the dour college president, Chaplin, who became enraged that his students had broken the college’s strict code of decorum. He was also convinced that students had been tippling some strong New England rum. Marriner, the historian, argues that Chaplin was not an anti-abolitionist, but that such a drunken disturbance of his college’s sober quietude could not be tolerated. The next morning, President Chaplin gave the students an earful. It’s not known what Chaplin specifically said, but the students weren’t having any of it. They sprang to their feet to demand he retract his remarks. Chaplin later retorted that he meant every word he’d said.

Chaplin promptly called a faculty meeting to demand the suspension of several of the student ringleaders, pending further investigation. Professor of Mathematics and Natural Philosophy George Washington Keely, and Calvin Newton, Professor of Rhetoric and the Hebrew Language, supported the President but urged caution. Keely believed Chaplin should apologize for his vitriolic remarks. After a tense week of classes, Chaplin delivered a statement to the student body assembled in the college’s chapel.

“We are happy to find, on inquiry, that none of you were chargeable with drinking ardent spirits or wine on that evening,” he said. “The noises which we heard from the dining hall excited fears that some of you were actually inebriated, and that all present have made some use of ardent beverages. We feel it to be a fit subject of congratulation that such apprehensions were erroneous.”

But Chaplin continued to condemn the boisterous celebration, insisting Independence Day should be observed in the same manner as the Sabbath, with “sober and chastened” joy, and without any amusements or entertainments that “unfit the mind for the holy intercourse with God.” He insisted his intention wasn’t to “deprive” the students of “any real enjoyment,” but that “happiness does not consist in mirth and jollity,” and “true joy is always serious.”

Then he shoved in the knife.

“[Y]oung men who are obtaining a college education may justly be expected to have a taste somewhat more elevated than that of the common herd of mankind,” Chaplin proclaimed. “Can you be surprised, then, that after all the pains we have taken to refine and elevate your feelings, some of you have a taste so low and boorish, that you can be pleased with noises which resemble the yells of a savage or the braying of an ass? For you to pride yourselves on doing that which a boor, a savage or a brute may do as well as you is truly contemptible.”

Chaplin concluded by announcing that two ringleaders of the joyous constitutional convention had been expelled and six others given long suspensions.

The students were livid. On July 17, they submitted a petition to the faculty that stated the President had “misrepresented” the Independence Day gathering and his remarks were “harsh, severe, and undeserved.” They’d heard from faculty members, they added, that Chaplin’s intent wasn’t just to scold and punish them for the meeting, but “also for certain misdemeanors for six months past.”

“We are willing on all occasions to receive reproof when guilty of violating the laws of the college, but we think we have a right to expect that such reproof will come couched in at least respectful language,” the students wrote. “We consider that our characters as students of this college, and as men, have been unjustly injured and we ask redress. Those of us who were not present at the celebration on the Fourth of July feel it due to ourselves to ask how far we are implicated in the address, and what instances of misconduct were there referred to.”

Professors Keely and Newton urged the President to restrain his emotions, and they expressed sympathy with the students, many of whom stood out as well-behaved, conscientious and devoutly religious young scholars. But Chaplin refused to back down. Finally, at a meeting of the college trustees on July 30, 1833, President Chaplin submitted his letter of resignation. The trustees had attempted to mediate the dispute, in vain.

In a response to Keely and Newton’s earlier criticism of his behavior, Chaplin and his son-in-law, Professor Thomas J. Conant, accused the two of undermining the President’s authority and hinted at a longstanding feud between the two faculty factions. “We do not accuse these professors of betraying us,” Chaplin and Conant wrote. “They do not deserve to be ranked with Judas, who betrayed his Master, nor with Peter who denied him. The course they have pursued resembles rather the conduct of the other disciples, who, when the Master was arrested, had not the courage to stand by him, but forsook him and fled.”

Marriner also suspected that previous disputes over discipline of students, as well as resentment over nepotism, could have contributed to the tension. In addition to Conant, the President’s son-in-law, Chaplin’s son, John O’Brien Chaplin, had recently been promoted from tutor to professor.

The trustees ultimately determined the two sides were irreconcilable and had no choice but to accept the resignations of Chaplin, his son and son-in-law. Shortly afterward, they appointed Rev. Chaplin to serve on the board of trustees, a post he held for many years.

But the trustees also refused to approve the formation of such a radical organization as the student Anti-Slavery Society. A few months later, students submitted a proposal to start a Colonization Society, part of a national, white-led movement to send African Americans to colonize West Africa. That group was also rejected, but only because the college lacked the funds to support it.

Many of the abolitionist students went on to become leaders in their communities. There was Waterville native William Matthews, a best-selling author and founder of the Yankee Blade, a long-running literary and family newspaper; Rockwood Giddings, who became President of Georgetown College, a Christian school in Kentucky; Ivory Quinby, a businessman and mayor who helped found Monmouth College, in Illinois; Elias Magoon, a talented preacher, lecturer and author; and James Upham, a minister and editor of the Boston-based Christian Watchman and Reflector and the Virginia-based Religious Herald. Another abolitionist student, Jonathan Forbush, later established a “French Mission” to serve French Canadian immigrants. Forbush reportedly died of pneumonia after doing humanitarian work in a blizzard.

It wasn’t until 1858, three years before the outbreak of the Civil War, that college faculty permitted the formation of an Anti-Slavery Society.

Andy O’Brien is the communications director for the Maine AFL-CIO. You can reach him at andy@maineworkingclasshistory.com.